Corporate Week as a Strategy for Leadership Communication

Thousands of books have been written about business communication. I suspect most CEOs could write their own about what works and what doesn’t. Here at Fedcap, we have co-created an excellent model for ongoing leadership communication on a regular basis.

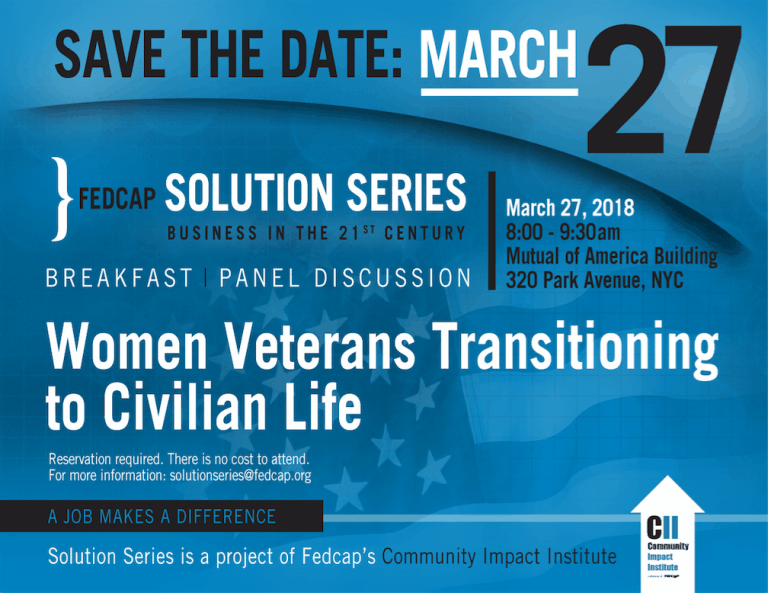

We are a large and complex organization with over 4,000 employees working throughout the United States. We are comprised of a growing number of “brands”, each with its own identity, and in common, a commitment to eliminate barriers to economic well-being. We do our work through four practice areas—education, workforce development, occupational health, and economic development, along with our Community Impact Institute (CII), which is the research, innovation and “think tank” arm. Corporate Services provides every practice area and company with the Financial, Technological, HR, Engagement and Facilities infrastructure required to succeed. These elements of Fedcap- practice areas, brands, CII and corporate services- augment, support, and strengthen each other to advance our mission.

Needless to say, given this organizational structure, good communication is paramount to our success. Our executive team thought long and hard about the many processes and structures that needed to be in place to facilitate effective communication. One model we designed is called Corporate Week.

Corporate Week is an in-person gathering of leaders from throughout the organization. We gather four times a year to discuss our strategy, pipeline, finances, impact, and environmental trends, ensuring we are prepared for and “ahead of the curve” on any challenges that may come our way.

While it takes a lot to bring people together in one place, I feel strongly that it is essential. The people in these meeting rooms are some of the brightest minds working today, and just being in the room together generates amazing dialogue, offers opportunity to wrangle and disagree, and ultimately, creates an opportunity to identify potential solutions to some of society’s toughest problems. Guests are invited to enhance the discussion and ensure our thinking is cutting edge.

Once the week is over—and it is a busy week with five core meetings and many opportunities for additional small group discussions—our leaders take the learning back to their respective teams. This brings the strategy and structure closer to the frontlines—an essential building block for trust, motivation, and success. And ultimately, this success manifests itself in relevant, sustainable impact for those we serve and for the community at large.

What are some of your best practices around communication with agency leaders?