Structure in Service to Innovation

A Google search of “the importance of innovation” will turn up more than one hundred million hits related to business.

“While centralized authority was the driving force of business in the 20th Century, brainstorming, innovation and lower level decision making characterize emerging companies of the new century,” writes Alex Cooper, in “Innovative Organizational Structure” at SmallBusiness.com. He points out that organizational structure must be intentionally designed to generate innovation from teams and individuals. Mike Sicard, CEO of USI emphasizes the importance of structure serving as a vehicle to advance strategy. He emphasizes that a good structure accelerates what you are trying to accomplish as opposed to serving as a barrier.

Kristi Hedges, contributor to Women at Forbes.com tells of a leader who “kept a plaque on his wall of everyone who had tried and failed—spectacularly—in the pursuit of an audacious goal.” Every executive saw the names when he or she interviewed for the job, and each time they came into the leader’s office. The tone was clear: we value risk taking and reward it as we seek to innovate.

It’s widely known that innovative companies are more creative, collaborative and productive. We also know that innovative companies achieve sustainable growth, renewed competitive advantages and ongoing customer relevance. In other words, they make a more substantive impact. The challenge to leaders is structuring the organization to tap these traits within staff.

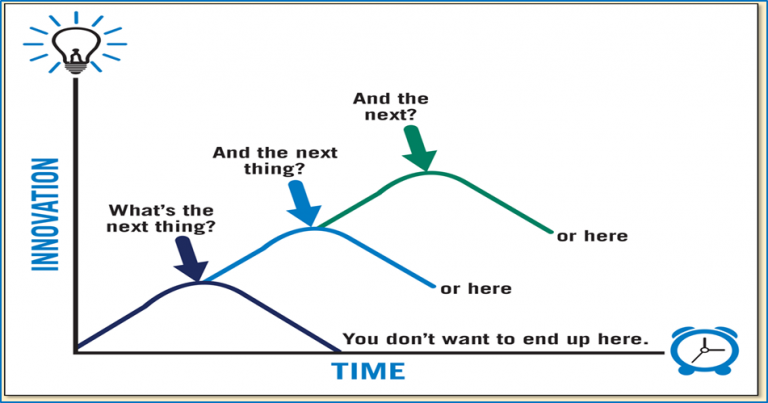

The structure of The Fedcap Group has been intentionally designed to advance innovation resulting in sustainability, relevance and impact. In 25, 50, 100 years from now, we expect to be continuing to provide smart interventions that make a lasting difference in people’s lives.

- We have developed four major areas of practice: Workforce Development, Education, occupational Health and Economic Development—each led by experts allowing us to influence state and federal policy and program design.

- We have developed a growing body of expertise and accompanying evidence-based interventions in improving the outcomes for specific populations including the justice involved, children ages 0-6, youth transitioning from foster care, adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities and individuals on public assistance. This allows us to focus our efforts on building effective program interventions that meet specific needs.

- We have combined with a growing number of top-tier mission-driven organizations. These companies engage the practice area and population expertise to design new programs and expand services, impact and diversify revenue streams.

- We have built an array of corporate services with state-of-the-art technology in the areas of Finance, HR, IT and Facilities with the capacity to support companies in their growth and impact efforts.

And to ensure we effectively leverage this structure to design models of service that can create lasting impact, we have implemented a “Cube” approach to program innovation and business development supported by a robust technological platform. The platform manages information related to each opportunity from lead through cash in the door and creates consistency in business development processes.

With this Cube approach, practice leaders, company executives, population experts and corporate services staff come together to create responses to requests for proposals from government funders, to design models of intervention to test with foundations and to prepare bids for managed care organizations. Each piece of the cube works synergistically to accomplish the goal—a winning proposal/bid.

Through the cube we are building a culture where everyone is responsible for innovation and everyone is responsible to help design an approach that has the potential to fundamentally improve outcomes for individuals we serve.

I welcome your thoughts.